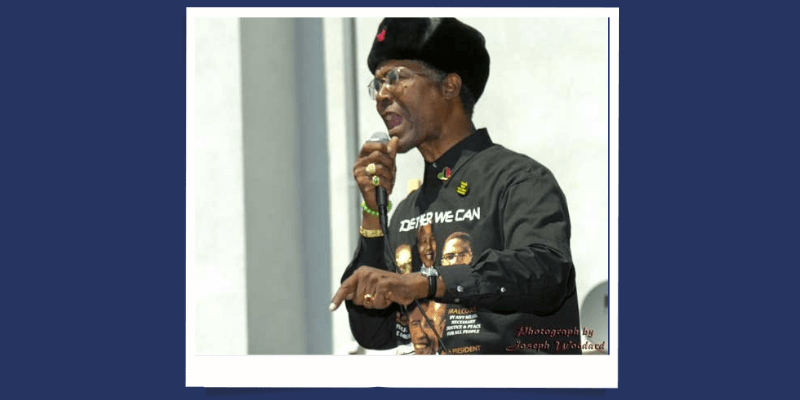

(Sept. 14, 1944 – June 2, 2022)

Photo credits: Brooke Anderson and the BEA Initiative

Dr. Henry Clark was an iconic leader of our environmental justice (EJ) movement–founder of the West County Toxics Coalition and for many years, the most vocal opponent of the Chevron Oil Refinery in his community of Richmond, California.

There are many stories of Dr. Clark’s powerful leadership and legacy, including his being a member of the first chapter of the Black Panther Party in his youth. In memory of his inspiring leadership through many decades, here are some personal anecdotes and reflections.

I first met Henry when I moved to the Bay Area around 17 years ago–to help groups connect their campaigns against dirty energy industries, with the struggles of communities where oil, gas and coal are extracted (i.e. the Alberta Tar Sands and Appalachia). Working with many other organizers, we convened the Mobilization for Climate Justice (MCJ), one of the early efforts to build alignment among mainstream environmental policy groups and labor unions, with the leadership and priorities of EJ communities taking climate action. The massive disparities in funding and staff capacity between big green non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in San Francisco and EJ groups in the East Bay–and the lack of collaboration due to siloed campaigns, clearly defined the need for such alignment, underscoring the deep racialized division that continues to exist across the climate movement today.

My friend David Solnit set up a meeting with Henry, Torm Nompraseurt of Asian Pacific Environmental Network and Jessica Tovar of Communities for a Better Environment, and we discussed how to invite allied organizers with San Francisco’s environmental NGOs to support the Richmond coalition’s campaign against the expansion of the Chevron refinery. I clearly recall Henry’s advice – saying that, in order for large environmental groups like the Sierra Club, Greenpeace and others to build relational trust with EJ communities, they needed to take the BART train over to meet us in the community spaces of Richmond and Oakland.

“The rich need to travel to our communities, to learn about our stories and struggles on the frontlines, for us to work together in real solidarity,” he advised. “We don’t need to be going over to their fancy downtown SF offices, just because they have all the money, because we just don’t have the time.”

So we began calling meetings in the East Bay, with skilful facilitation provided by comrades like adrienne maree brown, Sharon Lungo and Carla Perez. At first it was like pulling teeth – getting our young white organizer friends from SF to show up after their 9-5 jobs. But after a few weeks of meeting EJ and Indigenous community groups in the East Bay and listening to the stories of veteran organizers, respect replaced mere curiosity, and we hit our stride in organizing MCJ. It is worth noting that MCJ played a key role in supporting the Richmond community’s early victories against Chevron’s expansion plans. MCJ became the laboratory that eventually birthed the Climate Justice Alliance in the following years. MCJ also launched some of the first nationally-coordinated mass direct actions on climate change across Turtle Island, which amplified an intersectional, climate justice framework for “Systems Change, Not Climate Change!” in the lead up to the UN Climate conference in Copenhagen in 2009. Between 2007 and 2010, MCJ rolled out teach-ins, trainings, and mass direct actions against California’s largest industrial polluter in the backyards of the poor.

Anytime we hit critical challenges, we sought Henry’s advice. Like when Chevron asked the San Francisco NGOs if we would call off a widely advertised “march and action” we were planning, if they committed to hosting meetings to address community concerns.

“Hell no!” was Henry’s response. “Those greenhouse gangsters won’t be buying us off with coffee and donut consultations, while they continue to poison our communities,” he stated, drawing a clear line in the sand for many young market campaigners from the world of mainstream NGOs who are often naively misled by “talk, loot and pollute” corporate social responsibility (CSR) schemes. Henry was old school that way, reminding us what it meant to practice the EJ principles in our day to day.

Henry, Principles & Practice

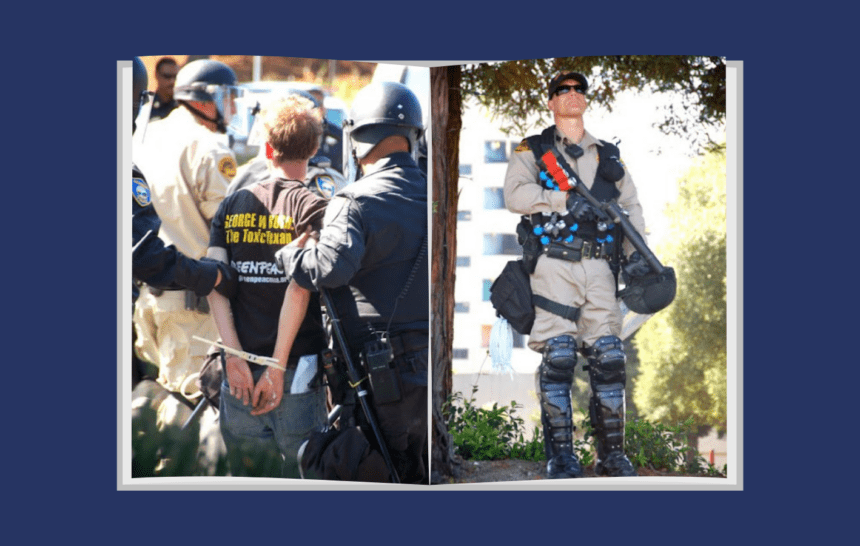

Another time, the Richmond Police invited us into a sit-down meeting to discuss an upcoming march and action we were planning for months. We knew it would be a large turnout and we had facilitated multiple direct action and blockades trainings in preparation for the day. The cops were worried about the anticipated numbers and wanted to set conditions for our taking over the streets, public spaces, obstructing traffic etc. The cops told us, “If you show up with more than 200 people, you can have one street lane going in your direction to the refinery.”

From the very start of the meeting, I had observed how much respect and deference the cops were showing Henry. I’d never witnessed cops being so courteous to grassroots activists before and attributed it to Dr.Clark’s decades of community service and leadership. I was also amused by the large, colorful assortment of donuts and beverages the Richmond PD laid out for us at our meeting table. So it was a bit of a surprise when Henry responded sharply with, “We’ll be there with thousands, we will take the entire street, and take as many streets as we need, as these are our streets!” Henry then demanded the cops not wear riot gear or use tear gas, and if they chose to wear riot gear, to not carry shields and have their visors up. With a local, activist lawyer as witness, he then had the Richmond police chief sign this agreement on paper for us to bring back to the larger coalition.

On action day, more than seven local, state and county police detachments were deployed, but–on Chevron’s instructions–were highly reluctant to arrest any of our blockaders when we laid siege to the refinery by land, water and sea. Leading the U.S. Green Energy Trade delegation to the UN COP 15 in Copenhagen that year, Chevron were loath to have their greenwash exposed by arresting protestors at the biggest GHG emitting facility in California.

Henry, Reverend Ken Davies, and other community leaders had to force their way at the front gates for the cops to start arresting us.

When I think of Henry, many memories and lessons come to mind, including conversations we had in later years when he had to struggle with other local organizers and comrades around positions he had publicly taken. Some of these were painful conversations where we noted our own differences, but always stayed open to get into the “grit” – inner conflicts in our movement family where we need messy, sometimes unpleasant conversations about practice, accountability and responsibility.

One thing I know is that Henry was always committed to working out such differences and willing to struggle through complexity and contradiction with his comrades in ways that underscore a popular, present-day sentiment of “we shall not cancel us”.

One of the last times I engaged with Henry was at a national gathering of EJ leaders and allies to discuss the federal clean power plan. After patiently spending the day listening to a large roomful of leaders and policy experts discuss the challenges of federal climate regulation hardwired to allow pollution trading and other market mechanisms, Henry had enough.

Late in the afternoon during the closing plenary, he stood up and lambasted apologists of the Obama administration for selling us out to polluting corporations–his favorite term, “greenhouse gangsters.” His direct attack on the President made many uncomfortable. Some colleagues even requested I intervene as the session facilitator, suggesting I cut Henry short and take away his mic.

But my instincts advised differently.

I listened as Henry spoke 10 to 15 minutes beyond his allotted comment time and only walked up when I anticipated his conclusion, to put my hand on his back.

Thinking about that moment today, I am so glad I trusted my intuitive compass–showing Henry the respect he was due when he chose to speak an unpleasant truth to his peers. He reminded us to stay principled in the face of corporate collusion and neoliberal policymaking.

Lessons from Henry

Organizing with Henry, I’ve learned that in order to build powerful movements, we will always need to boldly and respectfully struggle through our differences over strategies, tactics, and ways to navigate the myriad challenges and opportunities we face. However, learning to do so gracefully, guided by our principles and without interference of ego, self-interest and privilege, is key to the growth of our collective power.

As with our born families, we must learn to love and care for each other despite our differences, committing to discuss, debate and jointly overcome any impasse over time. Aligning practice in both personal and political selves is the only way we can grow our power to stop those threatening the Earth and all her children. The stories, memories and lessons of movement ancestors, fallen warriors, and our transitioned comrades who’ve dedicated their lives to defend and serve future generations can help us navigate the complexities. They also provide the best guidance for future generations to tackle future storms, floods, fires, pollution, pandemic, police, prisons and other forms of structural violence coming their way. As the ancestor song goes, Henry Clark was a freedom fighter, who taught us how to fight, and we’re gonna struggle all day and night until we get it right…

Rise in power, Dr. Henry Clark! We remember you for your courage and dignity in confronting injustice. We remember you for your unwavering solidarity with all international struggles. We know you will always be by our side as we march and take action against these global systems of colonial extractivism, greed and destruction.

Thank you!